[voltar ao menu principal] [página do Voto-E] [página do concurso]

Privacy International 2003 Contest

Stupid Security Measures for Brazil's e-Vote

Act One: Preemptive Sampling

CIVILIS and Forum do Voto-E

http://www.votoseguro.org

- 0. Background information

- 1. Introduction

- DREs

- Software certification and validation

- Three acts by a post-modern Janus

- Software certification and validation

- 2. Enabling vote recount

- SIE: A system based on DREs

- Regulating the auditability of SIE

- A legislative proposal

- Regulating the auditability of SIE

- 3. Historical Accident

- A lopsided tale of corruption

- The cookie jar

- Downfall of a fox

- The cookie jar

- 4. Showdown my vote

- Political juggling

- Preempting chance

- Downfall of a hope?

- Preempting chance

- 5. Epilogue

- About the authors

Index

0. Background information

Brazil is a democratic federative republic, with the State organized in three levels. Municipalities under states (one federal district), under the federation. Unlike in other democratic federative republics - whatever that means - electoral matters in Brazil are solely under federal law. State and municipal electoral laws are forbidden by the constitution. This has historical reasons. Tales of election fraud speckle our country's history since early independence (1860's), when the State was still a kingdom, newly separated from Portugal. These cases kept gaining density, particularly after Brazil became a Republic in 1889, culminating in a "revolution" (a small one, with a few dead) in 1930, aimed at getting rid of flawed electoral process which did not allowed for the typification of electoral fraud, the so called "bico de pena".

As a result of the 1930 revolution, a branch of the Judiciary Power was formed, named The Electoral Justice. A bureaucracy in charge of all elections for public offices, it turned out to be less of a branch of the Judiciary and more of an oxymoron for the democratic principle of balance of powers, despite, or perhaps because of, two long interruptions in democratic ruling, form 1932 to 1945 and form 1964 to 1985 (http://www.ccc.commnet.edu/ stuweb/~quiterio5816/History.htm). Its mission being to enforce federal electoral legislation, in practice it was given the legislative power to regulate on how the measures or dispositions in such laws shall be enforced or fulfilled, the executive power to run the elections it regulates, and – last but not least – the judicial power to judge itself with regard to its two other functions. Brazil's Electoral Justice is hierarchically organized as a top federal court, named Superior Electoral Tribunal (TSE), and state courts named Regional Electoral Tribunals (TREs), with its original mission becoming a trinity of functions.

Following up on its informatization program, started with a centralized databasing of registered voters in 1987, TSE began specifying, bidding, buying and deploying to TREs, for use in all public office elections beginning in 1996, Direct Recording Electronic Voting Systems (DRE), called in Brazil "urnas eletrônicas". We will henceforth refer to the DREs chosen for deployment at official elections in Brazil by the acronym "UE". They are basically Intel PC platforms with flashcard storage, sold by Procomp (subsidiary of Diebold Inc., Ohio) and Unisys Brasil.

image 1: photo of an UE by Procomp from http://www.politica.pro.br

The use of UEs in brazilian elections grew progressively to reach the totality of precincts in 2000 and 2002. Voting in Brazil is compulsory, there being today around 117 million registered voters, all of which were to vote in one of the more than 400 thousand UEs deployed for nationwide elections. That's Brazil's e-vote, which have yielded president Lula's all-time world record for votes given to an elected president, according to some boasted local media reports (http://www.lula.org.br/index1.asp). That is not a mere curiosity, for it may be setting trends, as we can figure by following the news on the modernization of electoral processes worldwide (http://www.psr.keele.ac.uk/election.htm).

1. Introduction

DREs

Among electronic voting machines, DREs are peculiarly amusing because they do not materialize a voter's vote. A DRE employs no paper, no electronics, nor any other media or means to register individual votes. It does not openly tally individual votes. It does not hold electronic representations of individual votes beyond the time frame the system's designer deems necessary for totaling the votes entered. Once the voting period is finished, all that remains available from a DRE machine are the totals per candidate, including undervotes (brancos) and overvotes (nulos) entered, and some statistics, for a particular election.

A DRE solves the problem of electronically implementing the commonly held modern democratic principle of vote secrecy by doing away with election auditability. A DRE trades the possibility of recounting individual votes for vote secrecy, obtaining such secrecy through the easiest and shortest path. That is, through the path which mistakes integrity assurance and authorship for just the latter, as the predicate of such desired secrecy. Because of this, DREs rely solely on software certification and validation to inspire, in the technical sense, trust in the accuracy of the results they can yield. This trust will, obviously, be comparable to the rigourousness, thoroughness and care with which such certification and validation are done.

Software certification and validation for 400 thousand computers is undoubtedly not an easy task. In a democracy able to defend itself, the reliability of such complex process will hinge simultaneously on the independence, competence and efficacy with which the various steps of this process can be carried out, assuming their completeness. It will hinge on sufficient means to expose or neutralize, to an acceptable degree of certainty, not only design, implementation and operational flaws, but mainly the possible collusions amongst any subset of agents against its values and principles. With DREs, the reliability of an electoral system will, therefore, depend on a delicate balance of risks and responsibilities among its human agents.

Software Certification and Validation

According to Brazil's federal electoral law in place, the task of certifying and validating the softwares in the UEs and its system rests with the political parties running for the election (Lei 9504, art. 66). As the indenter, owner and operator of the UE machines and its system, as well as the regulator which writes the rules for this certification and validation, the Electoral Justice is responsible, in theory and practice, for the terms and conditions under which the political parties are to pursue this task.

As explained before, TSE is a supreme court responsible for protecting the constitutional and legal rights of voters, at the same time that it also happens to be the operational arm of the State responsible for enabling and enforcing such rights, thus becoming their main potential violator as well. Therefore, it can only play balanced acts with its two faces if it is not to fail any of its functions. Since these functions make up a kind of holy trinity mission, failing one will mean failing the others. Thus, TSE's two faces are like the faces of Janus, the Roman god of beginnings and portals. If one face has to turn right, the other face shall not want to turn left.

image 2. Janus, from Encyclopedia Larousse

Has TSE been playing balanced acts? Well, depends on how one observes. One has to follow both faces at once to find out. This, plus the fact that contemporary mainstream media and cultures seems chronically incapacitated for looking at both faces of Janus at once, is what makes this story so interesting. Trust inspired by technical sense may not mean trust inspired by psycho social sense.

Three acts by a post-modern Janus

Some of the acts played out by this post-modern Janus at Brazil's political stage are worthy of notice, for their didactic value on the interface between information technology and political power. We selected, for Privacy International's 2003 contest, three of these acts. Our choice was based on the central role of some proclaimed security measures and on such didactic value they feature. For this article we chose an act we call "Preemptive Sampling". The reader is invited to judge by him or herself as to the efficacy, boldness and possible effects of its central character. The other two acts are the "Parallel test" and the "Self validation" acts.

2. Enabling vote recount

SIE: a system based on DREs

With complete informatization attained through the deployment of UEs at the totality of precincts for any official election, the voting system in Brazil set up by TSE and known as SIE (Sistema Informatizado de Eleições) works, in general lines, as follows (http://www.tse.gov.br/).

Initialization: The electoral official responsible for a precinct (sessão eleitoral) sets up the voting system by initializing the UE which has been prepared for that precinct by the corresponding TRE, in the presence of designated political party supervisors. The UE software holds a list of names and pictures of candidates for the elections taking place at the municipality of that precinct at that date. Upon initialization, the list of names of candidates is printed out in a paper ribbon by a printer built into the UE's CPU (larger module in figure 1). The CPU is placed in a closed booth and connected to the control terminal (smaller module in figure 1) by a long serial cable, which is placed a few meters away in a desk where electoral officials will sit. The picture of a candidate is shown to the voter who chooses said candidate, as part of the voting stage in which the voter is to confirm his vote.

Vote: When someone comes into the precinct to vote, he/she is identified through an official list of voters registered to vote in that precinct, issued by TSE from its central voter registry database, against a personal document (which does not bear a photograph of its owner), issued by the precinct's corresponding TRE upon registration. The electoral official enters the voter registration number into the keyboard in the control terminal, and some voting software at the CPU checks whether that number belongs to that precinct and whether such voter has already voted in that election. If that number belongs and has not yet voted, the numerical keyboard of the UE's CPU is set to receive that voter's votes.

Finalization: At the end of the voting period, normally at 5 pm, the electoral official responsible for the precinct finalizes the vote by commanding the system to end voting. The UE software then records on magnetic media (a 3.5" diskette) a digitally signed electronic version of that precinct's voting report, called "boletim de urna" (BU), which is a list of candidates who have received at least one vote, followed by the number of votes he/she has received, and the number of overvotes and undervotes from that precinct. It also prints copies of a textual version of the BU in paper ribbon. These copies have to be signed by the electoral officials and handed out to the party representatives who supervised that precinct's vote.

Polling: The diskette with the BU is then sent to electoral "informatics poles", which are the end nodes of a computer network set up for polling the elections. Such poles are connected directly to the TREs, and these to TSE through a VPN with a tree topology. There is usually one pole for each group of approximately ten medium sized municipalities, set up at some electoral registrar. The task of these poles is to validate the BUs received, to transmit them to their upward TRE node and to store electromagnetic media and flow control papers and equipment. The TRE nodes are responsible for polling the results of municipal and statewide elections, to transmit polled results and BU votes for the presidential election (if applicable) to the root note at TSE, and to proclaim electoral results (except for presidential elections, done by TSE). TSE also runs a TCP/IP report service, for delivering on-line partial results for all the elections taken place in the country, through a specialized http browser developed and freely distributed for this purpose.

Regulating the auditability of SIE

Modern States don't compare in scale to classical greek cities. Therefore, modern democracies are based on a fragile adaptation of its basic mechanism – elections, raised to stand on a tripod whose legs are the processes of voting, polling and auditing. A weakness in any of these three pillars can fault the reliability of modern democracy's basic mechanism. The fascination with technology nurtured by our contemporary civilization has allowed decision makers and public officials to introduce information technologies in social processes under sole justifications of efficiency, as if the molding of social processes by any gauge of efficiency would risk no drawbacks.

This shortsidedness, of which the preemptive sampling act is a case study, has weakened the third leg of the tripod sustaining Brazil's fragile democracy. In describing this act, we will mention some decisions taken by those in charge at TSE for regulating existing electoral legislation, on their lobbying for modifications on this legislation "due to evolving informatization", on their judging of own conduct on this matter in a manner that can be construed as reckless for this third leg, and on how they have gotten away with it in the face of public opinion and legislative oversight. One of our hopes is that such a stance can be better challenged, not only in Brazil but in other scenarios to come from sorcerer's apprentices, with the help of honors this case may get from the Privacy International's 2003 contest.

Nationwide elections are held every two years in Brazil. For all elections held under federal Law 9504, that is since 1997, TSE had been interpreting very narrowly, through its regulations, article 66 of this Law, which establishes audit rights regarding information technologies involved in SIE. Article 66 of Law 9504 says (http://www.pt.org.br/assessor/PL4604.htm, translation by this author).

"Art. 66: Political parties and their coalitions will be able to inspect all phases of the processes of preparation, vote and polling of elections, including the UEs and the electronic processing of polling results, being granted to them previous knowledge of the computer programs to be used."

In all these elections, only some of the code, and access to its source code, was made available to designated party inspectors under extremely limited technical and legal circumstances. But just enough to generate headlines in mainstream media suggesting the fulfillment of article 66.

Furthermore, these regulations had no provision for independent validation of whatever software was inspected, regarding its integrity between inspection and deployment (the central character of the "self-validation" act). In addition, any legal challenges to such narrowness, on the face of contradictions and paradoxes it has arisen, have been either sidetracked through legal technicalities or answered with outright debauchery. Some of the technicians, scholars and politicians involved in this inspection game and legal challenges have co-authored a book, so far available only in portuguese in pdf format, entitled "Burla Eletrônica" (http://www.brunazo.eng.br/voto-e/arquivos/BurlaEletronica.pdf), narrating some tales and details most of which collected, documented and presented by themselves in a seminar held at Brazil's National Congress in May 2002.

A Legislative Proposal

All in all, nationwide elections held in 1996, 1998, 2000 and 2002, the last two done totally through UEs, offered no assurance of the integrity of individual votes cast through these machines. No mechanism for the recounting of individual votes and no meaningful software certification and validation procedure has been yet featured, as thoroughly described in "Burla Eletrônica".

Since 1998, when the first elections under Law 9504 were held with its software audit provisions disdained by electoral authorities, some citizens and politicians have voiced their concern on the possible adverse effects this could have for brazilian democracy. In response, they have joined and proposed, through the Federal Senate in 1999, a new electoral law addressing more positively the weaknesses of a DRE-based electoral system whose owner, regulator and judge had been reluctant to consider. The idea was to force back the materialization of individual votes, while retaining as much as possible from the UE equipment and software already designed, contracted, built and deployed.

This proposal of legislation stated the following (translation by this author):

- All UEs shall print a voter's vote on a ballot of paper, and let the voter see the content printed on the ballot before the voter confirmed his or her vote;

- The printed ballot shall be automatically deposited on sealed ballot bag, for further tallying;

- After the voting period, a sample of 3% of the UEs would be drawn by open sortition, for their attached ballot bag to be tallied and the results compared with the corresponding electronic BUs.

According to that proposal, a voter is not supposed to touch his/her ballot, but to see and confirm if votes printed in it coincide with what was keyed in. The ballot printer is supposed to be a module designed to be attached with screws to the voting machine, connected to it by a built-in serial port connection. The printed ballot is entirely seen through a glass before an extra last "confirm" cuts it from a paper reel inside the sealed printer, letting the ballot fall by gravity into a bag attached to the printer, which is sealed to the printer – and both to the CPU – with adhesive labels hand-signed by electoral officials. That proposal was filibustered for almost two years by the political coalition in power at the time, until some unexpected incident opened a very narrow opportunity for its approval.

3. Historical Accident

A lopsided tale of corruption

This incident, which stirred up a lot of public indignation with the hypocrisy surrounding contemporary political life, was a political scandal at the Senate that came to be known as the Senate's electronic panel scandal. We choose to narrate it here in some detail for two reasons. First, it is emblematic of the obstacles facing a democracy for sensitizing lawmakers on the importance of sound computer security measures regarding social processes which come to rely on information technologies. Second, its pivotal role in the legislative struggle from which emerged the central character of this act, a (stupid) security measure put into law at the last hour, turning upside down a thoroughly planed similar measure proposed for that law.

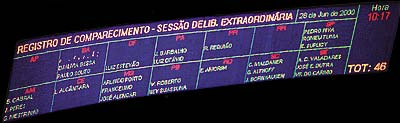

One junior senator was to have his mandate revoked by his peers in a secret Senate vote, due to mounting evidence of his involvement with kickbacks, fraud, corruption and money laundering. He remained unrepented and defiant to the last minute, coming out of that vote, in a special closed session of the Senate held on June 28, 2000, without his mandate and vowing to avenge his defeat. This was the first case of such type of punishment in Brazil's senatorial history.

Then, later, the president of the Senate confided to a reverenced federal prosecutor that he knew who voted for and against the corrupt junior senator on that vote, supposed to be secret. This prosecutor, who claimed to have recorded an unauthorized audio tape of that confession, leaked the story to the press without disclosing the tape. The president of the Senate denied the content of the press leakage and a watergate-type scandal snowballed from there. (a major brazilian newspaper's chronology of the scandal can be found in portuguese at http://www.estadao.com.br/ext/especiais/tempestade/tempestade.htm).

The cookie jar

The Senate staff and the company contracted to build, deploy and maintain the Senate's electronic voting system, gave their word that such leakage was not possible, since the system was "100% secure". Meanwhile, a political foe of that Senate president was elected to succeed him, in a fierce political battle. The new Senate president then ordered the premises sealed and a serious audit. An university team (Unicamp) did the audit job, under a lot of pressure, and a public investigation by the legislative power was set up.

This audit and public investigation exposed an electronic voting system (that of the Senate, made to order for the Senate as specified by the Senate) rigged with built-in backdoors and vulnerabilities, allowing, for example, the system operator to vote, before the day was over, for senators not present during voting sessions, through the infamous "botão macetoso".

image 3: photo by Joedson Alves/AE from the senate session of June 28, 2000

It turned out that this system, according to Unicamp's audit, allowed for 18 different ways to leak the list of individual votes in secret ballotings. A trail of traces of leakage of the votes on removal of the junior senator was also found. This leakage employed the most cumbersome and convoluted of those 18 ways: recompiling to set up yet another backdoor in the application, running, reverting after. This trail pointed to the system operator.

The downfall of a fox

The company responsible for the system then changed slightly the discourse: "100% secure" now means "built exactly to specification". Secure in the software engineering sense. The small fish came up accusing the next fish in the feeding chain, until the Senate informatics director confessed having commandeered subordinates to do the "fix" at day-break on the date of the vote, following orders from the Senator then presiding the Senate. The former Senate president ended up getting the heat. He then confessed, disavowing his denial, and was forced to resign his senatorial mandate to avoid the same fate of his junior colleague, which would have legally blocked his political rights for eight years. All this on nationwide televised hearings of unbeatable audience rates. (speculations about the untold part of the story can be found in http://www.cic.unb.br/docentes/trabs/Brazilvote1.htm)

4. Showdown my vote

Political Juggling

That's when public opinion came to openly admit that information technology products are not made nor operated by angelical beings, and that naiveté is the only moral wrong in politics. People could have hinted that before by reading history books, or even hacker books for that matter. But it took such a tragic scandal for most to connect the dots, revealing a sense of indignation which was veered by the group proposing a new electoral law, then in hibernating mode at the Senate, as public pressure in its favor. The Senate's electronic panel scandal has served to show the value of the materiality of individual votes in TSE's System (SIE). Where a bug can sneak in to leak votes others can to swing a race, and the proposal begun moving by April 2001.

However, for perhaps the same reasons that most people don't like to learn lessons from history books, people tend to fade their memories about collective indignation. So that by the time the proposal for rematerializing votes in SIE got to be voted in the Senate, in October 2001, very few were alarmed when sixteen amendments were submitted at the last minute, by government parties in response to a request from the president of TSE. One of them was to change item 3 of the proposal, regarding the sampling of UEs for the purpose of auditing elections through printed ballots.

All but one of the amendments submitted through proxies by TSE's president were voted into the proposal, with hasty votes form the government coalition under the basic argument that "nobody knows about electronic voting better that TSE". TSE's president had previously asked the senators to wait for his contributions to the proposal, having said that electoral legislation "of technical nature" is not subject to the constitutional one year delay to take effect. Shortly before the one year deadline for the 2002 elections, however, he changed his mind about the delay waver for matters "of technical nature" and asked for urgency, sending his request for those sixteen amendments the day before the proposal was to be voted under urgency in the Senate, two days from that deadline.

Preempting chance

The proposal went on to become federal Law 10.408, signed in January 2002 effective January 2003, having stalled in the Deputy's Chamber after the hasty changes suffered at the Senate. It was not in effect for the last election, in October 2002, the next being in October 2004. The original item 3, regarding the sampling of UEs for the purpose of allowing the auditing of individual votes through printed ballots, now reads (translation from this author):

"Art. 59 - § 6º On the day before the election, the electoral judge, in a public audience, will draw three percent of the precincts of each electoral zone, respecting a minimum of three precincts per municipality, which will have their printed ballots counted for comparison with the results presented by the corresponding electronic DRE report"

Why did the head of the Electoral Justice surreptitiously asked lawmakers to change the draw for the 3% ballot audit sample of UEs from after the election to the day before?

In the apocryphal document sent to the senators requesting it, the reason for this amendment was: "for technical reasons". No later explanations were given as to what these reasons may be. And worse, nobody seems to care. On the other hand, with unauditable software, any innocent looking instruction for preparing UEs for later audit, such as to turn power on with a certain antecedence, or to enter certain initialization keystrokes for checking whether the the plastic bag is fixed to the ballot printer with both openings correctly aligned, can signal to the system that the electronic BU in that particular UE shall not be rigged.

If there is a collusion between some political party and the developer or deployer of UE's unauditable software, an early draw for the 3% sample destined for printed ballot audit will permit the preemption of the audit's intended effect. For example, by allowing that BUs from the other 97% of UEs, upon absence of signal indicating upcoming audition, have a fixed percentage from one candidate's votes subtracted and added to another, when voting ends and before outputting the BU. UE's software are deployed around a week before the vote, replicated in trickled down fashion from TSE. So that a collusion may include opinion poll makers secretly raising data to determine the percentage needed to swing a race, while discounting this percentage at poll result releases. One sign of such arrangements would be a wild divergence among opinion polls, exactly as happened in some state gubernatorial elections in 2002, such as in RJ, DF, and RS states (http://www.estadao.com.br/eleicoes/noticias/2002/out/24/349.htm).

From here on we refrain from delving further into the risks of collusion facing a system like SIE for which any effective auditability provisions have been resisted. Since this document is intended primarity for people with some computer security background, we prefer to explore, instead, the difficulties and chalenges mainstream culture raises for experts trying to sensitize lawmakers on the importance of sound computer security measures, and trying to get their society to hold them accountable for the consequences of their decisions. With this choice, we feel that we can better highlight the drama of our central character in this act – the preemptive sampling security measure, highlighting the stupidity factor Privacy International has set out to gauge.

Downfall of a hope ?

We can not know the real reasons for the security measure which preempts sampling for audits, cast as an amendment to the original ballot-printing measure. But we can reason about the possibilities. The only effectiveness we can find for such a measure, is for the security of a dishonest operator. If the uncofessable reason is the focus of the security – that of the swindler, Law 10.408 as passed still leaves him with considerable risk. Chances remain that an electoral official in some backland precinct may fail to correctly understand "preparation for audit" instructions, and his BU report may end up involved in some discrepancy at the printed ballot sample audit phase of the vote. We can not know if that was the focus, but we can observe that TSE, and all the TREs for that matter, do not like this measure, even with the preemptive sampling of article 59 in Law 10.408 they asked. How can we observe that?

With some moods turned sour due to the off-again, on-again need for a one year delay for electoral "technical matter" legislation to go into effect, TSE's president offered some consolation for those who wanted to anchor their trust of SIE on material ballots. He announced his court's decision to "voluntarily" implement ballot printing in some 5% of the precincts for the 2002 elections, "as an experience". TSE then chose two small states (SE and DF) and some other precincts in large state capitals, for that 5% "experience". As the 2002 election approached, they managed to misinform the public, with taxpayers' money channeled for electoral education initiatives, about the reason for ballot printing and the differences in operating modes of UEs with and without ballot printing.

In educational TV ads they ran, omitted was the fact that ballot-printing UEs required an extra pressing of the "confirm" button (the green button in figure 1) at the end of the vote, for the voting process to complete with the cutting off of the paper ballot. Election rules forbid election officials from entering the voting booth with some vote in progress, and the omission happened even in the two small states going ballot-printing in full. Most of the precincts chosen to run on ballot-printing UEs were inflated with an above-average draft of registered voters (in the two small states going ballot-printing in full, the number of precincts was cut, despite significant demographic growth from past election year), for an election date piling up six different races (president, two senate races, governor, two deputy races). The result was long lines in these precincts (besides voting in Brazil being mandatory, SIE is who picks the voter's precinct), 3 to 4 hours waiting under 35-40 degrees Celsius heat. The electoral authorities then flocked to the media to blame, in the words of the president of the Federal District's electoral court (TRE-DF), "this stupid security measure" (ballot printing) for the chaos (http://www2.correioweb.com.br/cw/EDICAO_20021013/col_cor_131002.htm).

The "modernization" of our electoral system has been entirely financed by the Interamerican Development Bank, with practically unauditable contracts. Not even the designated party inspectors could ever see the insides of a ballot-printing UE. No one outside Janus' house knows the terms of the contracts for their supply, and thus nothing about the quality assurance provisions for this supply. All we can know is a widely circulated report by TSE stating an abnormal degree of failure of ballot-printing UEs during the 2002 elections, compared to the old non-ballot-printing ones. (http://www.tse.gov.br). Intriguingly, we can find plenty of statements by electoral officials through media records BEFORE the 2002 election took place, expressing their opinion that ballot-printing UEs would show a high degree of failure, besides being unnecessary, despite the fact that all of them already had, balot-printing or not, a built in report printer.

5. Epilogue

We hereby respectfully submit, as our candidate for the most stupid computer security measure in the world, the amendment to the security measure accused of stupidity by election officials, the amendment anticipating the draw for the sample of UEs destined for printed ballot audit to the day before the vote, as stated above in a translation of Art. 59 - § 6º of brazilian federal Law 10.408, named here the preemptive sampling measure.

In the Federal District's gubernatorial election of 2002, decided by less that 0,1% of the votes, there were abundant signs of fraud. The candidate who barely lost asked for a recount of printed ballots, and the court (TRE-DF) voted unanimously not to recount, sticking to the dubious electronic tally, with the printed ballots hanging in bags attached to all of its UEs in storage (DF was one of the two small states with ballot-printing UEs in all its precincts). The case is pending at TSE at the time of this writing, but no electoral court in Brazil has ever officially admitted to the possibility of electronic voting fraud.

Meanwhile, TSE's president has submitted a proposal to Congress asking, among other things, for the audit measure through printed ballots to be revoked, based on the conclusions drawn in his widely circulated report, that is, on the "unreliability of ballot-printing UEs", plus an alternative to auditing through printed ballots called "Parallel Test", the central character of act two of this series. Even with preemptive sampling, printed ballot auditing still bothers decision makers at TSE. As for the acceptance by Congress of the proposal to ban ballot printing, the chances have to be set to high if we consider past lobbies by the Electoral Justice on the legislative power. We may have to accept our "bico de pena" back, this time in a virtual version.

The act presented here has been coadjuvated by some patriotic brazilians who, as concerned cybercitizens, hoped to capitalize on the Senate's electronic panel scandal for mending a broken leg in the tripod sustaining their democracy. Before their hope faded into oblivion, they got a boost from the chance of being heard by the public who might be touched by the outcome of Privacy International's 2003 contest. Good luck to us all, for no one in this world is safe today from the consequences of our collective fascination with technology as panacea.

About the authors

This document was produced through a cooperation effort among participants of CIVILIS.

CIVILIS is the name of a core group of 12 activists from all over Brazil, organized around an open discussion list with about 200 subscribers and its web site, http://www.votoseguro.org, regarding electronic elections in Brazil, its process and reliability. The person responsible for the domain name of that site, Amilcar Brunazo Filho, who is also its web master, participates in CIVILIS and took part in the elaboration of this document.

At this time, this core group is under preparations to found a non-government organization for better channeling its collective vision, concerns and proposals.